Photo courtesy of NOAA

From sailors to kayakers to swimmers, there’s one thing everyone who spends time on the ocean has in common: a stake in protecting it. For decades human activities have been taking a toll, and there’s every reason to believe the worst is yet to come. Many experts believe it is no longer a question of if it will reach a crisis point, but how soon and what we can do to head off the worst of it.

The good news is there are still opportunities to mitigate the damage. In fact, a huge number of dedicated organizations are fighting back—and some have even employed really cool sailboats to do it. Here’s a glimpse into the myriad interconnected problems facing our oceans, the efforts being made to fight them and the role individuals like you can play in all of this.

MARINE LIFE

Let’s go back in time to perhaps the most famous green marine movement of all—Greenpeace’s “Save the Whales” campaign. Nearly 50 years ago, dedicated advocates brought dwindling whale populations to the forefront of national conversations. In the context of today’s sea acidification, plastic pollution and increasingly frequent natural disasters, saving one type of animal may seem like a sentimental drop in the bucket. However, this advocacy, directly and indirectly, led to decades of efforts to track and improve whale populations, and the campaign’s record of success goes far beyond just keeping these majestic creatures alive for future generations. Though it may not be breaking news, the recent reports on world’s many species of whales are worth talking about.

Since 1950, the south Atlantic humpback whale population has made a remarkable recovery, jumping from less than 450 individuals to an estimated 25,000 today. In areas of the North Atlantic, the population is at pre-industrial whaling levels. Similarly, since the first studies in 1978, bowhead whale populations have been increasing at a rate of at least three percent per year and are approaching pre-whaling levels.

This is hugely important because whales are an integral part of the oceanic ecosystem at every point in their life cycle. When a dead whale carcass, for example, sinks to the ocean floor, it can provide sea life there with food for over a year. In killing and removing up to 90 percent of the world’s whale population, the whaling industry did untold damage to those ecosystems as well. And it’s not just deep-sea creepy crawlies that need whales. There is a process called a “whale pump” in which whales typically feed in deeper water and then excrete waste near the surface when they come up to breathe, thereby “pumping” nutrient-rich organic material to the surface, where it acts as a fertilizer for phytoplankton. Because phytoplankton are the basis for the marine food web, not to mention the main producer of atmospheric oxygen, this is a very, very good thing.

It’s all interconnected since the current overabundance of carbon in the atmosphere is also causing ocean acidification. Acidification results in less calcium carbonate in the water, which shellfish and coral need to build their exoskeletons and shells. This then threatens coral reefs, which in addition to the 25 percent of all marine life that depend on them, human beings also rely on reefs to act as natural breakwaters and protect coastal areas. In the United States alone several million people live in coastal areas shielded by reefs. If acidification and other pollutants destroy reefs, our coastal communities will face the consequences. In reality, both positive and negative adjustments to an ecosystem have widespread fallout—everything is related. More whales means more phytoplankton, which helps cut down on acidification, helping reefs to protect our shorelines.

When looking at the state of the world’s oceans as a whole, it’s worth mentioning whales are what’s known as “charismatic megafauna,” essentially a species that people are more inclined to care about because of symbolic value or popular appeal. A campaign like “Save the Whales” isn’t necessarily going to work for some obscure species of endangered zooplankton. The success of Greenpeace and other whale conservation efforts also aren’t indicative of a rosier picture overall. Coral reefs are still facing bleaching, sea turtles are getting caught in ghost fishing gear and a number of other whale species remain on the endangered species list, including the North Atlantic Right, of which fewer than 350 individuals remain.

Still, repairing even a single corner of the ecosystem helps the ecosystem as a whole, and advocating for change can make a difference. If you want a better, for the future of the ocean, make sure your representatives know it’s a priority.

POLLUTION

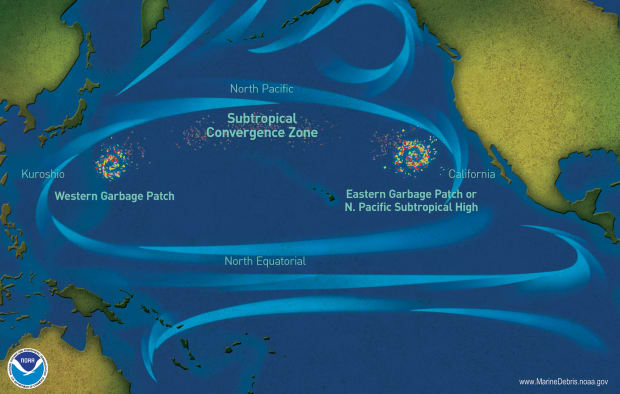

The truly big ticket marine crisis today is oceanic plastic, perhaps most famously exemplified by the Great Pacific Garbage Patch—a low-density trash accumulation zone created by the North Pacific Gyre. It also has four less famous but still destructive cousins in the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, South Pacific and Indian Oceans. The plastic problem is so pervasive it is estimated that by 2050 the world’s oceans will contain more plastic than fish. Approximately one million sea birds and around 100,000 sea mammals and turtles die every year as a result or ingesting or being trapped by plastic. Then there’s the issue of microplastics which end up in those same fish consumed by humans.

The start to fixing any problem is understanding it, and fortunately, there are a number of research organizations like the Rozalia Project, eXXpedition and the Sea Education Association working on understanding the human impacts on the ocean—and employing sailboats no less (rozaliaproject.org; exxpedition.com; sea.edu). Whether it’s the SEA’s fleet of tall ships or American Promise (formerly Dodge Morgan’s vessel of choice for his historic circumnavigation), sailboats have proven an excellent choice for this kind of research, since wind power is less disruptive and less toxic when operated in those same fragile areas where researchers are gathering data in. Noise pollution, resulting from rumbling engines and spinning propellers, also makes it difficult for many marine species to find and communicate with each other, which can impact the data being collected and the safety of the organisms.

Not surprisingly, sailing a research vessel can be a challenging task. One sailor aboard SEA’s Corwith Cramer said their crews contain some of the best sailors in the world—at sailing “poorly.” The reason for this is that the equipment for collecting water and organism samples requires consistently slow speeds that would never earn you a podium finish on the racecourse. As a result, before deploying equipment like their neuston tow, the crew, including both scientists and students, can be found scrambling around deck striking or backing sail in order to achieve a balance that yields exactly 2 knots of boatspeed. It is not a workplace for the faint of heart, but it’s worth it. The data collected by the SEA team in often hard to access places ends up everywhere from research papers to NOAA’s weather tracking.

That said, beyond the stray mylar balloon they might fish out of the water, vessels like the Corwith Cramer aren’t primarily focused on large scale ocean cleanup. That’s more the work of organizations like the Dutch non-profit The Ocean Cleanup (theoceancleanup.com), which hopes to tackle “large solid pollution.” To this end, it’s been developing technologies to rid the world’s oceans of their gyres of plastic via a two-pronged approach—filtering trash out of waterways before it finds its way into the ocean and the removing of plastics already in the ocean. The filtering part is done using something called the Interceptor system, which consists of a range of technologies, ranging from a low-tech “barrier” that strains trash out of the water to be collected later to the high-tech, solar powered “Interceptor Original,” which uses a conveyor belt to autonomously remove up to 100,000lb of trash per day. As for the oceanic plastic removal part of the equation, the process consists of a pair of vessels trailing booms between them to capture debris.

In the interest of efficiency, the Ocean Cleanup plans to use computational modeling to predict hot spots where its straining will be most effective. It’s no easy task because the trash gyres are so spread out, but in October of 2021, the organization announced its proof of technology tests on the “002” system were complete, and it would begin moving on to the actual cleanup phase, with plans to build an “003” system that will allow the project to be scalable with more systems potentially launched around the world.

A critical first step to tackling oceanic pollution is stopping the plastic before it washes out to sea

Photo courtesy of The Ocean Cleanup

Of the over 63,000lb of trash removed during the test run, founder and CEO of The Ocean Cleanup Boyan Slat said, “While it’s just the tip of the iceberg, these kilograms [of trash] are the most important ones we will ever collect, because they are proof that cleanup is possible.”

Another organization working to remove plastics from the ocean, including the abandoned plastic “ghost” fishing gear responsible for killing untold sea creatures, is the Ocean Voyages Institute (oceanvoyagesinstitute.org), based in Sausalito, California. In recent years, the organization has launched a series of sail-powered expeditions that have succeeded in removing hundreds of thousands of pounds of plastic from the Pacific Ocean. To ensure its operations are as efficient and effective as possible Ocean Voyages Institute uses a range of technologies, including UAVs, GPS trackers attached to debris by volunteer sailors on passage and satellite imagery to find debris that much more quickly. Once recovered, the plastic lines and nets are stored in the ship’s hold for proper recycling, up-cycling and re-purposing at the end of the voyage. As is the case with The Ocean Cleanup effort, the model is easily scalable.

“The oceans are the lifeblood of our planet and create two out of every three breaths we take,” said Mary T. Crowley, president and founder of Ocean Voyages Institute. “We depend on the oceans for our health and the health of our planet.”

Complementing these kinds of bluewater efforts, there are also a wide range of projects that focus on cleaning things up closer to shore, like Maryland’s “Mr. Trash Wheel,” Singapore’s WasteShark and England’s Water Witch. An especially large-scale example is The SeaCleaner’s forthcoming massive sail- and solar-powered ship, Manta, which will trawl for trash and have an onboard waste processing facility plus two satellite vessels to scoop trash in shallower water, targeting with coastal litter (theseacleaners.org). The project is still in the early stages with the ship slated to launch in 2025.

Of course, managing pollution at the shoreline is also essential to saving critical, vulnerable species and keep humans safe from their own waste. With this in mind a group that has been making a name for itself in this area is Wounded Nature-Working Veterans, a non-profit focused on cleaning up waterways and increasing domestic seafood production (woundednature.org). “At the time [our organization was founded] there were no nonprofits focused on hard to access coastal areas,” says Rudy Socha, CEO of Wounded Nature-Working Veterans. “There’s a lot of coastline that’s never cleaned up. In South Caroline alone there’s 2,950 miles of tidal coast land, and out of that, all of the public funding for cleanups goes to just the 141 miles of it that are public beaches.”

Socha adds the materials his group focuses on includes things like tires and treated wood that continue to leach toxic chemicals, like arsenic, creosote, mercury and carcinogens into the water. This is especially problematic because these same shores serve as nursery areas for fish, which can mean a reduction in the fish population that disrupts the entire ecosystem. One of the group’s specialties is tackling abandoned and derelict vessels that are often too difficult or expensive for traditional state organizations to remove. The vessels themselves often leach fuel, sewage, battery chemicals, fiberglass shards and more into delicate marine environments. Then there’s the fact that a good 40 percent of these derelict vessels include 4,000lb of lead in the keels. So far, the organization has removed over 130 vessels from the U.S. Eastern Seaboard. In addition to removing these pollutants, the organization has also laid 110,000lb of oyster shells to create new habitats for oyster larvae to attach and grow safely, refreshing the damaged fish nurseries.

So groups like Wounded Nature-Working Veterans and SEA have got it all covered, we’re all done, right? No, of course not. Even with the good they’re doing, cleanup efforts like those above don’t come without environmental costs of their own. There is some concern, for example, that The Ocean Cleanup’s offshore efforts will cause harm to microorganism populations in the areas where it’s skimming out plastic. Plus, it only collects surface-level plastics of a certain size, which leaves a lot of microplastics and other trash still out there. Beyond that, while these projects can reduce the impact of pollution in specific areas, they cannot keep up with the volume of plastic currently entering into the waterways worldwide. Just consider how much single-use plastic you use every day; almost everything you buy comes wrapped in it and much of what gets put into a recycling bin actually doesn’t end up getting recycled. It’s estimated eight million tons of garbage enter the world’s oceans every year—a garbage truckload every minute.

With this in mind, the number one best thing we can all do is avoid single-use plastic whenever possible. Get a reusable water bottle, bring your own bags to the grocery store and chose produce that’s unwrapped. Swap feminine hygiene products for a menstrual cup. Use Tupperware or aluminum foil instead of plastic wrap. Opt for soft drinks in cans instead of in bottles. The answer to stemming the tide of plastic in our waterways is in the supply chain.

Illustration courtesy of Noaa

SMART SHOPPING

In addition to basic plastic pollution, the global economy’s impact on the oceans take place in two related, but separate ways: via the goods people consume and the transportation needed to get those same goods from place to place.

First and foremost, transporting goods and materials around the planet by ship takes lots and lots of fuel—creating one billion metric tons of CO2 per year. And despite the International Maritime Organization’s 2016 mandate to move away from the most toxic kinds of fuel (bunker fuel or heavy fuel oil), the shipping industry still has a long way to go. The good news is there is a reason for hope, as the industry has committed to decarbonizing by 2050. This in turn has put pressure on shipping companies to develop the technology and infrastructure necessary to use a more sustainable option, like methanol. It’s been a difficult transition, though, due to a supply and demand chicken-and-egg problem—because there are so few ships currently powered by methanol, there’s no money to build the infrastructure; however, without the infrastructure, there’s no point in building a ship that runs on methanol. To break the cycle, shipping giant Maersk has ordered eight methanol-powered ships to help kick things into gear and make methanol cheaper and more available across the industry. It’s a good start.

We’d, of course, be remiss not to also mention the many other wind powered vessels and technologies out there that are stepping up to reduce the industry’s overall footprint—this is a sailing magazine after all! For starters, tall ships like Tres Hombres and the forthcoming Ceiba are bringing ultra-low impact options to the scene. However, tall ships aren’t exactly known for being fast or keeping reliable schedules, which poses a bit of a problem for those companies and goods dependent on more predictable supply chains. Enter technologies like the flettner rotor (a spinning cylindrical “sail”) and Seawing and Skysail’s auto-deploying kites—two options that can be retrofitted to a cargo ship to reduce fuel usage.

Companies like TOWT and Neoline are also building modern sailing cargo ships that are more efficient than the old tall ship designs. For more on the future of wind-powered shipping and the numerous inventive options in the works, see the Sept 2020 issue of SAIL or visit sailmagazine.com.

The other part of the consumerism equation is the shear volume of goods that are being produced. Informed consumers can “vote with their wallets” by choosing to go with products that are sustainably sourced, made from recycled materials, biodegradable or reusable. These days, there is no shortage of eco options; however, it’s also important to remember that, when it comes to shopping, the best way to do something good for the environment is often by doing nothing at all. Even the most amazing, carbon-neutral, sustainably sourced eco-friendly foulweather jacket still has a greater environmental impact than just using the one you already own. Investing in eco-friendly and carbon-neutral technologies and materials is important, but beware of companies that tempt you to buy things you don’t need in order to “be more environmentally conscious.” Remember that in addition to the item itself, which will almost certainly end up in a landfill someday, there are also the energy costs of the factory where it was produced, the raw materials that were used and the transportation necessary to get the product to the store where you bought it. As a general rule of thumb, look for green versions of things you need to buy anyway. Otherwise, use the things you already have.

Note, that there are a few exceptions to this rule. For example, if you don’t already have one, get yourself a nice reusable water bottle. While you’re at it, remind your crew to also bring their own water bottles with them when you go sailing. Unless you live somewhere without potable water, there’s no excuse for still using disposable water bottles in 2022. Similarly, if you’re still using a sunscreen with oxybenzone or octinoxate, it’s time to ditch that since these two chemicals have been shown to have a detrimental effect on coral reefs (not to mention that multiple studies have also found they can have an adverse effect on human hormone levels when absorbed through the skin). Most sunscreen brands make versions of their products that don’t contain these chemicals, making this is an easy switch.

On the other end of the spectrum from water bottles and sunscreen, a more complicated (and expensive) swap that still might be worth diving into right away is going electric with your boat or dinghy’s propulsion. As electric motors get better and battery ranges increase, more and more people are going green—often for reasons totally separate than environmental impact. Electric motors can offer fuel savings in the long run; they’re quiet and don’t produce fumes; and when paired with solar panels or a hydro generator, they allow cruisers more freedom to get off the grid. Not to mention that less fuel means less CO2 in the atmosphere, less acidification, more sea life and a healthier ocean.

Becoming Part of the Solution

Granted, the prognosis looks grim, and it certainly will take more than individual actions to solve the problem. Never forget, though, that there are lots of things that will make a difference if we all do them together. As mentioned earlier, things like political advocacy and reducing plastic waste or consumption can go a long way. Beyond that, if you’re looking to make an even bigger impact, here are a few ideas to help you get started.

1. Download the Ghost Gear Reporter App. This app from the Global Ghost Gear Initiative allows mariners to report derelict fishing gear so that local conservation agencies can come collect it. Fishing gear, especially nets, often get lost overboard and continue ensnaring fish, turtles and other marine life. By tracking any debris you see, you can do your part while enjoying a day on the water.

2. Volunteer or donate to an organization like Wounded Nature-Working Veterans. Groups that do regular cleanups throughout the year have a much greater impact than a single annual Earth Day cleanup.

3. Compost organic material. It might not be obvious, but composting is actually one of the best things you can do to help the world’s oceans. First, when organic food scraps are put in landfills, they produce methane, which is 25 times more potent a greenhouse gas than CO2. Second, composted material is turned into organic fertilizers that can replace those synthetic fertilizers that are high in nitrogen, a compound that washes into waterways and eventually the ocean, causing algal blooms that can choke the local ecosystem.

4. Bring ocean health to work. 11th Hour Racing Team—the IMOCA 60 race team sponsored by 11th Hour Racing—has organized a “Sustainability Toolbox.” This eight-step program includes a range of guides, tools and templates to help any organization become more sustainable. It’s suitable for companies and organizations of any size and in any industry. Visit sustainabilitytoolbox.org to get started.

September 2022