Painting reproduction courtesy of Heidi Coutu

Heidi Coutu and I had been enjoying the easy life of a warm July week moored in the inner harbor of Menemsha on the western end of Martha’s Vineyard. Heidi—then my girlfriend, now my wife—is a professional oil painter, and in the normal course of rotating her work, we had a vague plan to sail to Nantucket to pick up some of her art at a gallery there.

Our seagoing summer home, Bantam, was a 1973 C&C 35 Mk I. She was in good condition with new standing and running rigging, and I had installed a diesel in place of her original Atomic 4 engine. She had a single-spreader rig and a solid fiberglass hull with almost 6 feet of draft in a lead fin keel, and a large, spade rudder.

It was a sunny, warm day with a fresh, south-southwest breeze blowing in the mid-20s that would speed Bantam along the 38-mile rhumb line. Intoxicated by the day and the company, I skipped my usual pre-sail checklist: weather, plotted courses, and wind direction. And that is how the trouble started.

I usually lay my courses on a paper NOAA chart and then note current and wind direction/speed against the course so I can devise a sailplan to meet each leg of the trip. Bantam was equipped with a small handheld GPS, wind speed, and depth gauge. I used the GPS mainly to establish latitude and longitude and to monitor my speed over ground. My electronic package buttressed my older skills with paper charts and a hand-bearing compass. I was not concerned about accurately navigating the course to Nantucket because I knew the waters and had made this trip several times, the first being 27 years earlier.

Photo by John Maturo

We dropped the mooring at 10 a.m., headed out the narrow harbor entrance, and unrolled the 135% genoa but left the main furled. This was a “picnic” sail off the wind, and we would make good time without troubling to hoist the main.

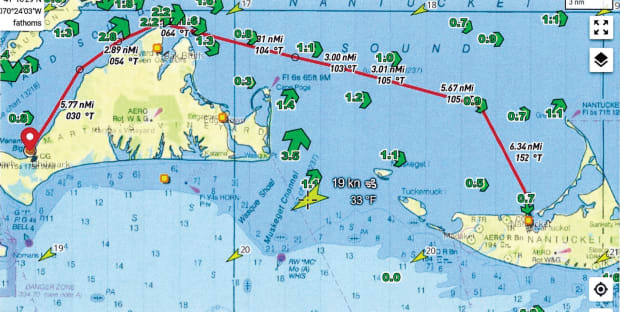

Bantam scudded along on a run making 8-9 knots with a good push from the current. As we approached West Chop, we followed the curve of the shore on a broad reach and scooted inside Middle Ground shoal heading for the next big course change at the apex of the Chop. At the turn, we hardened up to a beam reach to make 20 miles down course to G1, 6 miles from the entrance to Nantucket.

Pride always goes before the fall, and having deviated from my usual routine, I blithely cast off thinking only about the first leg. What could go wrong on a clear New England summer day with a south-southwest wind? To add to the ill preparation, we were dressed only in swimming attire, not even a T-shirt for me.

The wind increased into the 30s, and now that we were closer to the wind on a beam reach, we needed to reef the genoa. Despite a sturdy roller furler, reefing proved difficult, even using the primary winch on the windward side. We had waited too long and had the wrong sailplan, but I was stubbornly committed to a Nantucket landfall. I decided to tough it out knowing the boat was stronger than the man.

Heidi ground the non-self-tailing winch with the rail fully buried, and we managed to reduce the genoa to about 100%. The wind, the waves dousing us, the cold, the motion of the boat, and the extreme angle of heel did the dirty work, and the previously gleeful Heidi became seasick. We agreed that the best remedy was for her to go below, get out of the wet clothes, and climb into a sleeping bag in the quarter berth on the low side. But before climbing into the berth she needed to send my foul weather jacket up.

Illustration courtesy of John Maturo

She said I looked like Mad Max, hair standing on end. Every wave that broke over the bow hit me full in the face as I held the wheel. I was now hand steering over the crests to prevent crashing to the bottom of the larger waves. Despite these conditions, I was euphoric, racing along, hitting 12.9 knots once, close to but safely leeward of Norton and Tuckernuck shoals, until at the last course change at G1 we hardened up to a close reach.

By now the wind had increased to a steady 40 knots with higher gusts, the ferries had canceled service, and we were apparently the only ones on the water in this part of the sound. The last 6 miles from G1 to the breakwater at Nantucket was one long prayer that nothing would give way. We were near the edge of losing control with the cabin portlights half under water.

What to do? I decided it was too dangerous to reef again—the engine would not push us into port against this wind—and running off would mean going to Hyannis, 15 miles towards a lee shore. Bantam took this punishment making 9 knots down-course as I gripped the wheel and thanked her builders for putting together such a stout design.

As Bantam came to the stone jetties protecting the entrance to Nantucket, I fired up the engine and motorsailed to a mooring, rounded up, secured the pennant, and then with great effort rolled the sail to its stowed position. With Bantam quiet, Heidi recovered and came on deck as the launch pulled up. In dry clothes we touched land, headed for the first bar along the wharf, and promptly ordered dark ’n’ stormies.

Sipping our drinks, we overheard bar chatter musing about the insanity of the crew who had just brought that small sailboat into harbor. We nodded to each other, smiled, and enjoyed the elation of beating the odds. But ever since that day, I always go through my pre-sail planning routine because you never know what surprises the sea can conjure.

What We Did Wrong:

First, we did not chart our course and note wind direction and speed, did not check the weather, and did not dress appropriately. We reefed too late and should have had the main set so we could have doused the jib and reefed the main, which would have been a safer ride. I also had three smaller jibs on board for higher winds, but I couldn’t downshift to these shorthanded.

What We Did Right:

Bantam was equipped for offshore sailing and meticulously maintained, so nothing broke, nothing was amiss below, and everything worked as designed. I was well-versed in the route, navigation aids, and hazards, and visibility was good. I had decades of distance-racing experience and was in good enough shape to know I could handle the forces generated by this size of boat.

John and Heidi continue their adventures on a fully restored, offshore-equipped 1978 Baltic 39, Àshe, along with their golden retriever, Beau.

March 2023