Photo by Michael Mckenzie

My first job ever on a boat was picking weevils out of bags of sugar in preparation for a 1,200-mile delivery from the South Pacific island of Tonga to Opua, New Zealand, aboard a 43ft catamaran. Up to that point in my life, the sum total of all my sailing experience had been a single daysail.

Getting on that initial delivery was pure chance. After graduating college, I’d made various attempts at fulfilling what I called the “metropolitan dream” of getting a job and moving to New York City. In the end, though, I ended up moving back in with my parents toward the East End of Long Island and began working seasonal jobs in the wine industry. This in turn led me to New Zealand where I met the skipper and first mate of the 43-footer. Despite having grown up swimming and lifeguarding on Long Island Sound, one of the East Coast’s premier cruising spots, it took flying halfway around the world to get introduced to sailing. They invited me to fly to Tonga with them and sail back to New Zealand on their next delivery—an experience that changed the trajectory of my life.

During the 10-day crossing, I had a sense of such profound happiness I thought if I died then and there, my life would be complete. I’d reached a sublime state of existence. It simply could not get any better than this, I kept finding myself thinking.

When I returned to New Zealand and then, eventually, the United States, I kept on working for various farms and wineries. Whenever I closed my eyes, though, I would find myself remembering that passage. I saw blue in my mind as I buried my hands in the dirt. The problem was I didn’t yet know how to sail. So I got job at a marina in the Pacific Northwest and spent a year learning how on other people’s boats.

Next, I bought a boat of my own.

1976 Bristol 24

Anam Cara

Designer: Paul Coble

Bristol Yacht Co., Bristol RI

I found my first boat, the 1976 Bristol 24, Anam Cara, on Lake Champlain. At the time I barely even knew where Lake Champlain was, let alone that it was a sailing Mecca. All I knew was that it was connected somehow to the Hudson River, which led to the ocean. After working three jobs—waitressing, working at a wine-bottling facility and freelancing for the local newspaper—I bought the boat and moved aboard in the boatyard where she was on the hard, with nothing but a dinghy, a bicycle and a hammer.

The Lake Champlain sailing community took me in like a stray dog. Despite having never before touched a boat-working tool in my life, I somehow managed to install a bilgepump, beef up the chainplates, add backing plates to the deck hardware and get the engine running. I remember taking off the lower unit of the boat’s old Johnson 9.9 outboard with a group of people in the yard only to discover the impeller was gone. Once it had been replaced and the engine was properly cooling, the gathering crowd cheered. It was time to launch. It takes a village to raise a sailor, I remember thinking.

I launched the boat and spent the next six months sailing, living aboard and working yet more odd jobs. I convinced a sail loft to let me do some cleaning in exchange for a third reef point. I cleaned toilets in exchange for moorings. I helped restore an old IOR-era Morgan Heritage one-tonner. Anything to help make ends meet.

I also learned to sail engineless from an old sailor in what we dubbed “Bristol Bay.” It was a good thing since it meant when Anam Cara’s old Johnson gave out again, it didn’t matter. Lake Champlain and its many harbors are all so wide open, you can always find somewhere to drop the hook under sail.

In Burlington, Vermont, some local yachties found me a free mooring. I called them the harbor bros; they called me humble. I stayed there a month or so and would often go sailing on my neighbors’ J/24 and Corsair F-27. I took part in a 150-mile race to Canada in 35-knot winds that nearly destroyed my friend’s trimaran, but made us all much better sailors and much stronger as a crew.

Unfortunately, for all that it taught me, the Bristol also had some serious problems. Among them was a crushed mast step. Not good. Despite the fun I was having, I also wanted to leave Lake Champlain, and this was clearly not the boat to do it on. I, therefore, put Anam Cara up for sale and hung her up in the same boatyard near where I’d spent much of that season somewhat randomly anchored. (And where the marina manager had said I was welcome to row in and use the facilities for free.) The person who bought the boat ended up not only keeping her there but paying for the privilege—showing it pays for marinas to be nice to boat punks!

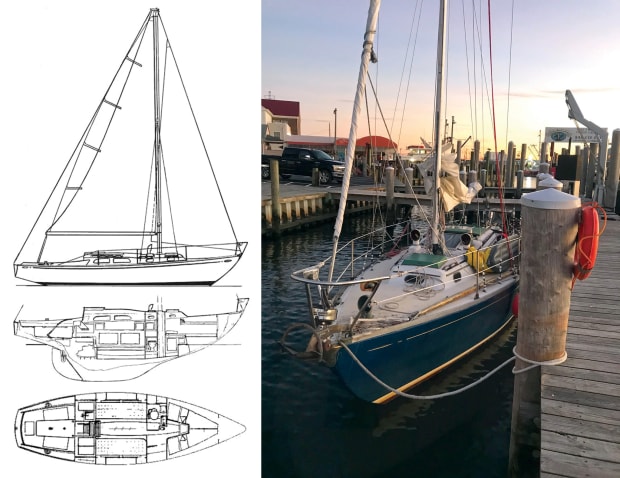

1968 Pearson Ariel 26

Vanupied

Designer: Carl Alberg

Pearson Yachts, Portsmouth, RI

A few days before selling the Bristol, I also bought the Pearson Ariel 26, Vanupied. There were no cheering crowds this time, and I was on my own getting the boat ready to splash. I launched the boat with a 4hp kicker that didn’t fit in the outboard well and a backstay that was about to fall apart. “Please don’t break, please don’t break,” I prayed aloud as I was sailing in 25 knots of wind back to the marina where I planned to fix the boat up again before leaving Lake Champlain.

When I finally arrived and removed the old bolts from the backstay chainplate, they literally crumbled in my hand. I swapped out the engine and modified the locker to fit a modern four-stroke. I found a used mainsail that was in much better condition than the one I’d started out with. I also picked up a used autopilot.

Even if I’d wanted to, I couldn’t have cut the proverbial dock lines when I left, since I’d had to sell my mooring bridle to a friend to cover the cost of my marina fees. Making my way south, tacking back and forth on the approach to the narrows leading to the Champlain Canal in the soggy remnants of a tropical depression, I ended up burning out my depthsounder. Nine canal locks and the entire length of the Hudson River later, I arrived alongside the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan. From there, New York Harbor spat me out into the Atlantic Ocean through the Verrazano Narrows.

The boat had no business being at sea. Because I didn’t have enough power in my house bank, I had to tape emergency AA battery-powered running lights to Vanupied’s bow and stern. My only source of electricity was a 30-watt solar panel. “Anyone else out here traveling the lonely blue highway tonight?” I naively called out on my VHF, as I watched a bevy of commercial vessels negotiating the shipping lanes farther offshore.

In the Chesapeake Bay, I rode a series of cold fronts to the northern terminus of the Intracoastal Waterway and promptly began my first transit. Sometimes I motored, but for the most part, I sailed. In Florida, I glassed in several defunct through-hulls, replaced the boat’s rigging and added more charging power. As I was doing so I also worked aboard a fake pirate ship for a while and helped out with a number of deliveries, up and down the east and west coasts of Florida and in Guatemala in an effort to gain yet more sailing experience.

Underway aboard Vanupied and northbound again, I remember leaving a little inlet in South Carolina. Every captain of every boat passing by was a man. Their crews were also all men, and the boats themselves all looked like they cost tens of thousands of dollars. I couldn’t help thinking it was an immense privilege simply being out there the way I was. Because who the hell am I? I’m just a girl from a small town on Long Island. I went to a state college in upstate New York. I’m an under-employed journalist. I’m a girl, alone, on an inexpensive little boat—a kind of a protest in and of itself.

Taking advantage of the sea breezes close to shore off the Carolina coast I continued on past the Cape Fear River. After that came a sporty 24-hour passage on North Carolina’s Pamlico, Croatan and Albemarle sounds. Arriving back on the Chesapeake, I drifted down with the current along the York River past a series of anchored oil barges.

It had been another successful passage. The boat had served me well. But it was time to move on again.

1978 Great Dane 28

Sohund

Designer: Aage Utzon/Klaus Baess

Sandersen Plastic Boats, Copenhagen, Denmark

While in Virginia, I got a job on a tall ship to save money for another boat. I also sold Vanupied sight unseen to a kid from New Jersey who would end up abandoning it in the same marina where I left it for him. Eventually, I bought Sohund, a Great Dane 28, a heavy-displacement cruiser built in Denmark. I also quit my job. It was too hot in Virginia to be laboring on anyone’s boat but my own. With $250 to my name, I began another refit.

With the help of my then-partner, I removed the diesel engine, sold it and added a sculling oar. With the money I got for the engine I was able to pay for a haulout and new rigging. To rerig the boat we used a traditional tall-ship method, making shrouds and stays out of galvanized steel wire parceled with cloth tape and served with tarred marline.

The plan was to eventually add an electric inboard, but that never happened. I later glassed in the shaft log and added a 2.5hp outboard on a transom bracket. Together we fabricated a set of all-new bronze chainplates and made our last passage together on Pamlico Sound. After a summer on the Chesapeake, during which I put a number of other finishing touches on the boat, including an open-source navigation system, an autopilot, AIS, new batteries, solar panels and a gimbaled stove, I was ready to go offshore again.

I sailed the Great Dane in up to 25 knots of wind and felt completely secure. Anything more than that, though, and my autopilot couldn’t handle it. The AIS proved invaluable, lighting up like a video game off the many busy ports I passed. I’d anchor off remote islands, hike to the other side and look out at the sea, amazed I’d just come from there. Staying awake for 18, 24, 30 hours straight began to feel normal. Same thing with tucking into a remote island anchorage at dawn, dropping the hook and passing out to sound of gulls and piping plovers.

As I made my way south, it also became clear what the boat would need if I was ever to go even farther offshore: things like a headsail furler, a better reefing system, a self-steering windvane and more safety equipment. The more I sailed, the longer the list grew. I began wondering: did I really want to keep on refitting this same boat, which I had already been working on for a year and half, or did I want something more?

Months later, I was getting the Sohund ready to sail back north, when I happened to look at Craigslist. I immediately noticed a Tripp 29 for sale, another strongly built Scandinavian-type vessel designed by the legendary Bill Tripp. The boat already had a Hydrovane self-steering windvane and roller furling. It also had an electric inboard motor and a rock-solid, keel-stepped mast. I knew it wasn’t going to get any better than this. I also knew that with the used boat market having become saturated thanks to YouTube and the advent of Covid-19, I’d have to act fast.

I was in Florida, and the boat was in Maine. I tried to get in touch with the owner to no avail. In desperation, I enlisted the help of some of my more famous sailing friends, including SAIL’s cruising editor, Charles J. Doane, (read more on that here) hoping it would get the owner’s attention. It worked.

1962 Tripp 29

Teal Designer: Bill Tripp

G. de Vries Lentsch, Amsterdam, Holland

The day after I heard back from Teal’s owner, Charlie, who is based in New England, was on his way to both look at the boat and (hopefully) purchase her for me. In no time, I found myself in a bidding war with a hipster from Brooklyn that ended in my paying $1,000 more than I’d planned, but I didn’t care. It was just money. That had never stopped me before. The main thing was this was the next step toward my ultimate goal of crossing oceans.

Meanwhile, still in Florida I now found myself wondering where and how I was going to sell Sohund. A friend had just gotten a free boat and was docked up in a little hurricane hole that I happened to be sailing past. I decided to stop in for the night and pay her a visit. While I was there she ran into a guy at the local yacht club who was looking to buy a 28ft ocean-capable boat to fix up and sail back home to his native Chile. She gave him my number. He called immediately.

“I just arrived in this country, and it is my only job to find my small ship,” he said.

“You’re in luck,” I said. “Because it is my only job to find someone to buy mine.”

That afternoon he bought the boat for my full asking price. We sounded the air horn to celebrate what is said to be the two best days in a sailor’s life—the day you buy and sell your boat.

Showing up in Maine soon afterward with my sea bag and trusted anchor, I had no idea what to expect having never before seen the boat I’d just purchased. After the initial shock of discovering how truly filthy Teal’s owner had left her, I set to work on a thorough survey and came up with a list of projects that needed doing before I could sail south again before the coming of winter—a deadline I only barely made!

Some time later this year Teal should be ready to sail to the Bahamas. If all goes well, Bermuda will be next, possibly aboard Teal, perhaps on another boat. I’ve long said I’ll need a boat a year until one sticks. How far I’ll go with this one remains to be seen. The one thing that hasn’t changed is my dream of crossing oceans under sail.

Before casting off lines in Maine, I installed a wood stove, refit the mast and running rigging, took delivery of a new mainsail and installed a new mainsail track. That last item makes it much easier reefing the main while sailing downwind, a problem aboard the other boats I’ve had. I also added a separate battery bank and solar panel for the electronics and house loads, and sorted out how best to charge the 48-volt system that runs the electric motor. There is, of course, still much to do.

“With my budget and timeline, I’m looking at years to have this boat completely ready to go,” I said to the salty old delivery captain on the boat next to mine when I first arrived. “I know I can’t expect a boat I bought for less than $10,000 to be ready to cross an ocean, but it’s a depressing reality.”

“A depressing reality, but you can’t live without it,” he said, stepping off his wooden black-hulled ketch with a cane in one hand and clipboard in the other. And he was right.

It’s now been five years of buying, fixing, sailing and selling old sailboats. It’s been eight years since that first passage to New Zealand. In the end, I don’t really care how long it takes, because having a safe, sustainable ocean-capable vessel is all I care about. I’m dedicated, and if I can’t cross an ocean now, damn it, I’m going to keep doing my best until I can. Because that’s what matters.

Ed note: In addition to being a regular contributor to SAIL, Emily Greenberg is also a dedicated blogger. Check out her work on the site dinghydreams.com

Photos by Emily Greenberg

March 2020