Photo courtesy of The Ocean Race: Vincent Curutchet /IMOCA

It’s been a long five years since the conclusion of the 2018 Volvo Ocean Race, and a lot more than the event’s name has changed. Here’s everything you need to know about this season’s premier ocean race before it kicks off on January 8.

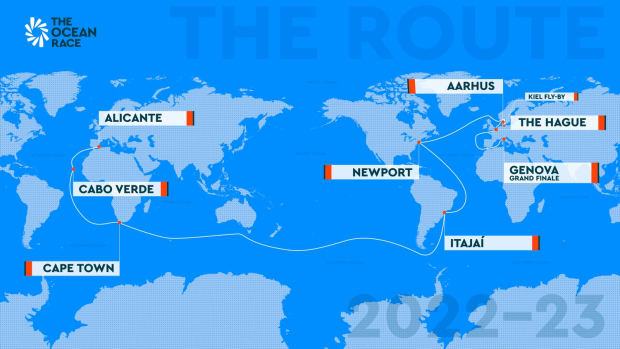

The Route

Illustration courtesy of The Ocean Race

Throughout every iteration of this event since 1973, The Ocean Race’s route has followed the same basic parameters: a circuit of the globe starting and finishing in Europe with stopovers scattered throughout. However, the route itself changes for every edition, and the stopover ports vary. This year, Alicante, Spain; Cabo Verde; Cape Town, South Africa; Itajaí, Brazil; Newport, Rhode Island; Aarhus, Denmark; The Hague, Netherlands; and Genova, Italy, are scheduled to host, and a “fly-by” in Kiel, Germany, creates an additional opportunity for fans to see the boats in race-mode while underway.

A discerning eye will note that this route is somewhat of a deviation from the typical Volvo Ocean Race routes of the past decade, which incorporated the Indian Ocean via stopovers in the Middle East, India, and Asia. It’s not clear whether this decision stems from a lack of willing host cities in the region, or the race organizer’s reluctance to put sailors back in waters that proved problematic in recent editions—including a fatal nighttime collision with a fishing vessel, the marooning of one team on a reef, and one memorable leg cancellation during which the boats had to be shipped from one port to the next due to piracy concerns. Instead, the teams will face off against a monstrous Southern Ocean leg, bypassing Oceania and stretching three-quarters of the way around the globe, south of the five Great Capes and through some of the planet’s most treacherous waters.

The Boats

The Ocean Race’s primary class is now the IMOCA 60, a box-rule class that’s been in production since the early ’90s, primarily used for elite shorthanded ocean racing such as in the Vendée Globe. According to 11th Hour Racing Team CEO Mark Towill, this means that sailors will have to be more in tune with their boats than ever. “When all the boats were identical, you pushed the boat as hard as you could. But with different designs in the race, you need to be more aware of your own boat’s limitations and strengths,” he says.

This approach has pros and cons—on one hand, winning a race in the design office doesn’t make for exciting spectating; on the other, different strengths call for more strategic racing—not to mention the introduction of technological innovations like foils. The IMOCA 60s will sail with five crew on board, including one on-board reporter and at least one female crew member. Since the 2018 edition, the race has mandated that every team include female sailors.

For the past few editions, the Volvo Ocean Race has been sailed in VO65s, a one-design class with a race-operated boatyard maintaining all the hulls, hardware, and sails to identical standards. Though VO65s will still race in the 2023 edition, they will be used as a training class, with all boats required to have at least three of their 10 crew members (plus an on-board reporter) be under 30 years old. The VO65 teams will also have at least three women as part of their crew and be allowed one additional crew member for the Southern Ocean leg.

Another interesting addition for this fleet is the VO65 Sprint Cup, which will add VO65 teams not competing in the full round-the-world race to some of the shorter legs and in-port series. Presumably, this has been done to provide more opportunities for underfunded teams and rookie sailors to get experience. But given how exhausted Volvo Ocean Race sailors typically are when they arrive at stopovers, it’s hard to say whether experienced teams will have the upper hand on these green short-course teams or not.

Photos courtesy of The Ocean Race: Amory Ross/11th Hour Racing

Racing with Purpose

One core theme for the race this year is a focus on sustainability. While building 60-foot fiberglass boats for grand prix racing seems somewhat at odds with this mission, race organizers have committed to some impressive targets. Just to name a few initiatives, this includes being a “climate positive” race—recouping more than the total of its greenhouse gas emissions with climate capture projects—and presenting 12 Ocean Summits to drive policy change. These summits, which began in 2019, have brought participants together to discuss issues facing the ocean, such as lack of governance and protection, and draft best practices and clear action items. The collected work will be presented in conjunction with the United Nations General Assembly in September of this year.

Another branch of the sustainability strategy is Relay4Nature, a partnership with the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the Ocean, Peter Thomson, to call on world leaders to increase their commitments to protect and restore the ocean.

Race organizers recognize that the ocean is their arena, and sailors have a stake in protecting it for generations to come. It’s no surprise that multiple competitors are racing with sustainability and climate action at the forefront of their campaigns.

Meet The Teams

The race’s main fleet will consist of five IMOCA 60 teams hailing from the United States, France, and Germany. Keep an eye out for upcoming announcements on the VO65 fleet, which had yet to confirm its roster at press time in early December. Per early reports, we may see teams from Mexico, the Baltic states, Poland, Austria, Portugal, and France on the start line.

11th Hour Racing Team/American

Can sustainability and performance go hand in hand?

Photo courtesy of the Ocean Race: Amory Ross/11th Hour Racing

Built on the DNA of the Vestas-11th Hour campaign from 2017-18, America’s home team, 11th Hour Racing Team, has put sustainability at the top of its priority list. While building a brand-new IMOCA 60 for the race, they compiled an extensive build report to help future projects reduce environmental impact. The boat will be skippered by Charlie Enright, while his long-time co-skipper, Mark Towill, will move into an off-boat role as Team CEO. The pair have been competing together since meeting during the 2007 Transpac when Towill was just 18 years old.

GUYOT Environment-Team Europe/French-German

Will history repeat for a pedigreed boat?

Photo courtesy of The Ocean Race: ILP Vision-Charles Drapeau/GUYOT environnemenT-Team Europe

Co-skippered by the French ocean racer Benjamin Dutreux and German Olympian Robert Stanjek, this team is built upon a winning combination from the 2021 inaugural edition of The Ocean Race Europe. Their boat, formerly owned by 11th Hour Racing Team as Alaka’i, has an impressive pedigree, most notably earning a second place in the 2016-17 Vendée Globe under the name Hugo Boss 6 while skippered by Alex Thomson. At the start of The Ocean Race, Dutreux will be fresh off an eighth-place finish in the singlehanded transatlantic Route du Rhum, suggesting great things in store for the team and boat.

Biotherm Racing/French

Will breadth of experience prove a winning recipe?

Photo courtesy of The Ocean Race: Ronan Gladu/Biotherm Racing

Another new boat on the starting line, Biotherm Racing will be skippered by Paul Mielhat. Mielhat is a regular name on the solo ocean racing circuit, and the multinational crew of eight seems to have experience in everything—the America’s Cup, Class40s, Olympics, the Vendée Globe, The Ocean Race Europe—but they only have one Ocean Race among the whole team.

Holcim-PRB/French

Can Escoffier defend his spot on the podium?

Photo courtesy of The Ocean Race: Eloi Stichelbaut/Polaryse

Though made a household name after a dramatic rescue in the 2020 Vendée Globe, Holcim-PRB skipper Kevin Escoffier has earned his stripes as the only skipper in the fleet who’s already brought home the gold in this race. He was part of the crew of the past two Dongfeng Race Team campaigns, which earned first- and third-place finishes. This team was a late addition to the race, only confirming their campaign in July. Despite limited time to prepare, Escoffier made time to squeeze the Route du Rhum onto the calendar this autumn. His fourth-place finish will certainly have the other teams watching this boat closely.

Team Malizia-Seaexplorer/German

Will having a team give a performance boost to this solo skipper?

Photo courtesy of The Ocean Race: Eloi Stichelbaut/Polaryse

This boat was launched just six months ago, with skipper Boris Herrmann using the Route du Rhum as its shakedown sail. Herrmann finished 24 of 38 boats, well behind other skippers that will be on The Ocean Race start line come January. However, given that the boat had little time to be broken in before the Route du Rhum, and that solo racing and crewed racing are two very different animals, it doesn’t follow that Team Malizia-Seaexplorer will be outclassed by the competition. Herrmann’s ambitions are to finish The Ocean Race, drop the crew off, and lap the globe a second time in the 2024-25 Vendée Globe.

Visit theoceanrace.com for more on the extensive sustainability program backing this race.

January/February 2023